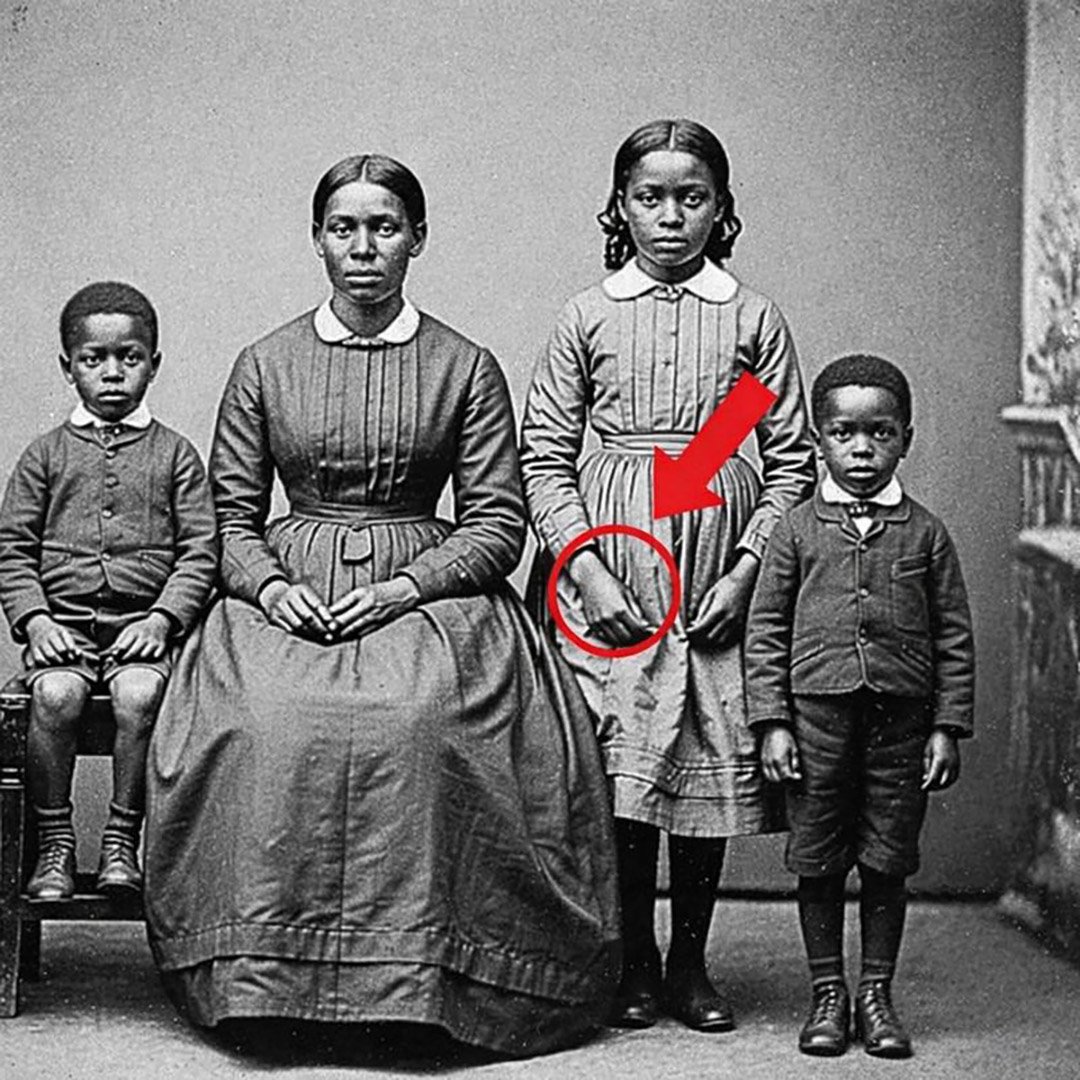

For more than 150 years, the photograph sat quietly among other family portraits from 19th century Mexico. Taken at a hacienda in Jalisco, it showed what it was meant to show. A wealthy family posed stiffly in a manicured garden, dressed in their finest clothes, carefully arranged to project order, status, and control.

At first glance, nothing seemed unusual. The composition followed the conventions of the time. Symmetry. Distance. Authority. It was only when the image was examined closely, long after it had lost its original purpose, that something unsettling emerged at the far right edge of the frame.

A figure placed where no one would notice

Ricardo Salazar, a senior curator at the Regional Museum of Guadalajara, had spent decades cataloging historical photographs when he came across the image again while digitising a private donation. As he enlarged the scan, his attention was drawn to a child standing slightly apart from the family.

The girl was young, no more than eight or nine. She wore plain work clothes. Her face was not fully in focus. The photographer had clearly prioritised the landowning family, leaving her presence softened and peripheral. She did not pose. She did not belong.

What struck Ricardo most was what the girl was holding. Clutched tightly against her chest was a folded piece of fabric. The way she held it was deliberate, almost protective. When the image was scanned at high resolution, the fabric revealed itself to be a small cotton dress. It was stained. Dark marks. Irregular blotches. A tear along one edge that showed signs of burning. These were not random marks. They were traces of blood and fire.

What history later confirmed

With the help of historian Mariana Guzmán, records from the San Miguel de las Flores hacienda were examined. The findings were devastating. The dress had belonged to Lucía, a five year old girl who had died only days before the photograph was taken. She had been badly burned while working in the kitchen with boiling oil. There was no doctor. No report. No ceremony.

The girl in the photograph was her sister Josefina. She was eight years old and already working as a domestic servant under the peonage system. The photograph had been taken just seventy two hours after Lucía’s death.

Josefina had saved the dress before it was destroyed. She cleaned it as best she could. Folded it. Hid it. And when the photographer arrived, she brought it with her. She stood where she would not be seen. She understood something powerful. That photographs endure. That one day, someone might look closely.

More than a century later, that moment finally arrived.

The image is now displayed in a museum, no longer as a symbol of wealth, but as quiet evidence of suffering, resistance, and memory. What was meant to glorify power instead exposes what that power tried to erase.

Sometimes the truth is not in the center of the frame. Sometimes it waits at the margins, until someone finally decides to look.